STABILITY OF SHOULDER JOINT

Anterior instability of the shoulder in abduction and external rotation (ABER) of the arm is characterized by lesions of the anterior capsule. Thus, the anterior structures of the shoulder joint are characterized as limiting external rotation as well as preventing anterior dislocation.

The glenohumeral joint does not have a deep socket. So ligaments are always under tension . The mechanisms of shoulder stability are different but it is effective: the humeral head which is slightly smaller than a billiard ball. It helds precisely centered on the glenoid which is about the size of a tea spoon (Golf T). It is amazing that such an arrangement can allow the shoulder to throw pull up lift punch and do gymnastics without coming apart.

The biomechanics of glenohumeral stability involve several static and dynamic mechanisms to achieve the balance between shoulder mobility and stability. Static stabilizers include the labrum and capsuloligements components of the glenohumeral joint. Fascial tissue is also consider as static stabilizer of shoulder complex.

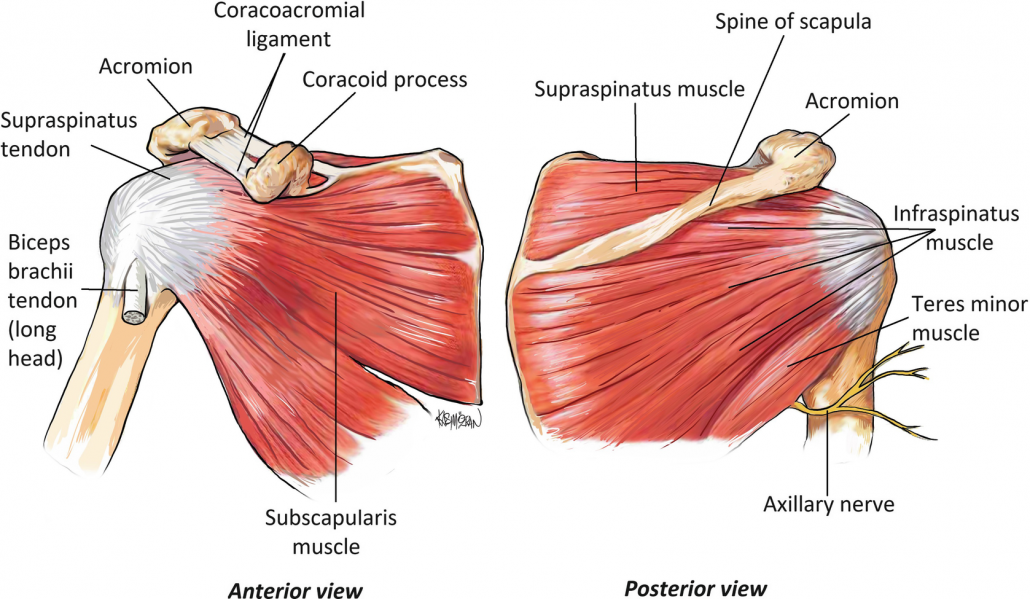

Dynamic stabilizers include the contractile tissues of the shoulder complex. The most well known structures are the rotator cuff muscles. which maintain centralization of the humeral head during static postures and dynamic movements. There are also the pericapsular muscles, which are very important for homogeneous shoulder movements while avoiding biomechanical misalignments, such as a shoulder impingement.

Clinical comentry:

The deltoid muscle (middle fiber in particular) acts to stabilize the humeral head against the glenoid cavity during arm elevation. On the other side the rotator cuff muscles control the humeral head into glenoid fossa.

Deficits in these forces couple can lead to superior migration of humeral head . Eventually reduction in sub acromion space. This reduction of space can compress the tendons and soft tissues within this space, leading to acute or chronic inflammation and dysfunction.

The glenohumeral joint is able to move through its extensive ranges of motion because of its construction and the contributions of the other joints within the shoulder complex. The acromioclavicular joint rarely is injured secondary to its strong ligamentous support. The good news is that the glenohumeral joint has more motion available to it than any other joint of the body. But the bad news is that its mobility and lax ligamentous support make it susceptible to injury or dislocation.

The rotator cuff provides active support to stabilize the humerus in the glenoid fossa. However the scapula is not secured directly to the thorax by a bony joint, the scapulothoracic joint is positioned and moved by its dynamic stabilizers—the trapezius, rhomboids, levator scapulae, pectoralis minor, and serratus anterior. These muscles form force couples to provide rotation of the scapula, just as the rotator cuff forms a force couple with the deltoid to rotate the humerus in the glenoid during arm elevation.

The scapula provides a stable base. From stable base of scapula the humerus moves and performs functional activities. Just as the scapular stabilizers hold the scapula in position for the glenohumeral joint, the rotator cuff holds the humerus in position to allow performance of upper extremity functions. This relationship between scapula and humerus movement is called scapulohumeral rhythm.

Larger muscles such as the deltoid, pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, and teres major are considered the movers of the shoulder joint and provide the power for forceful shoulder movements. If any of these muscles fail to function the shoulder is likely to injury.

To receive an regular update on website click on left side icon of whatss app and message PROACTIVE UPDATE.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!