Common error when preparing exercise prescription

Exercise for health. It is a mainstay in the toolkit of a physiotherapist. There is no other intervention that is as well supported by research. As movement specialists, we are aware of this. Because of this, we’re always looking for new workouts to try out or new methods to do the activities we already know and love. The appropriate exercise prescription is crucial, but there are two significant errors we make that have an influence on the outcomes.

⇒A Error We’re All Responsible for

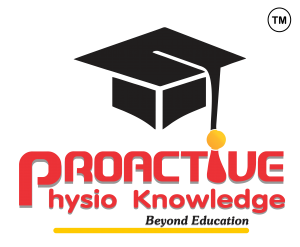

Giving our patients too many exercises is a common mistake made by physiotherapists. It’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking that if three workouts are excellent, six must be better. The issue is that providing our patients too many workouts might quickly overwhelm them and hinder their ability to heal.

If our patients do too many workouts, they will get fatigued and lose interest. It becomes more difficult to maintain consistency and see outcomes when the patient’s level of motivation is raised in response to our increased “ask.”

⇒Why is it so simple to mess up like this?

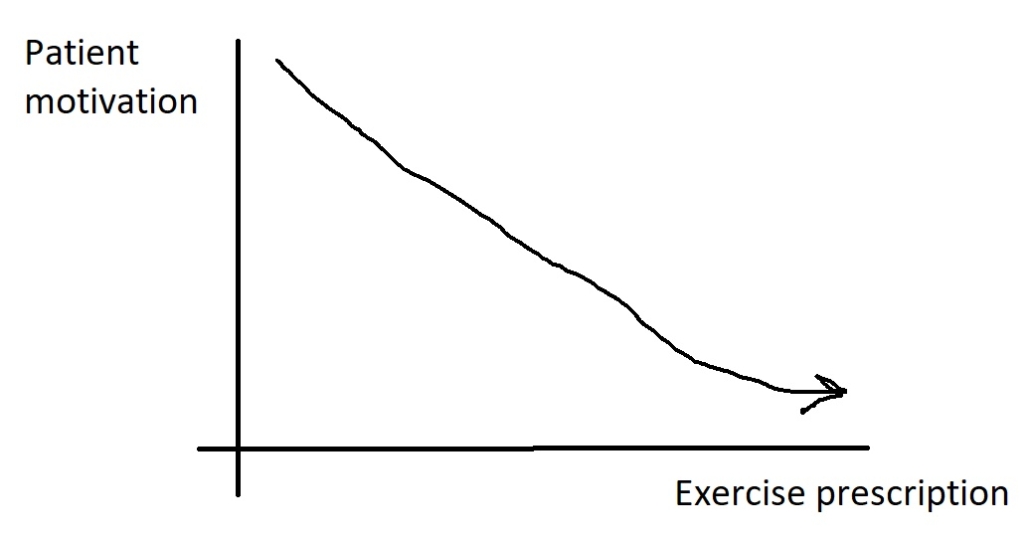

It’s simple to mistake the value we provide as therapists for the quantity of exercises we recommend. greater workouts equal greater value.

It’s a simple trap to be caught in.

The recommendation of exercise is linked to improving our feeling of self and reducing our underlying anxieties.

⇒An obvious flaw that affects patients’ success

We devote so much effort to teaching patients the “what” (which exercises to recommend) that we neglect to assist them with the “how” and “when” of doing workouts. Giving a patient extra exercise won’t help them attain their treatment objectives if they don’t complete them or execute them inconsistently.

⇒Why do we use passive methods of therapy on patients?

Over the last several years, I’ve asked myself this question a lot. I think the most of us, if not all of us, are staunch advocates of active rehabilitation, but there are those patients for whom we sometimes resort to passive therapy modalities.

What gives, though? I believe the issue is a breakdown in helping our patients develop consistency in their workout regimens.

The Spiral of Exercise Despair, in my opinion, is comprised of the following 5 steps:

Step 1: Therapy begins with exercises for the patient.

Step 2: The patient has poor compliance with the exercises or doesn’t perform them at all.

Step 3: The therapist continues to deliver exercises during subsequent sessions.

Step 4: The patient feels awful about not exercising and is evasive in describing the difficulties they are having.

Step 5: The therapist switches to passive therapy for the patient after seeing no improvement with exercise.

⇒Each patient is Unique

An 80-year-old inactive granny will need a totally different approach than a 28-year-old triathlon when it comes to exercise prescription. That is understandable, of course. However, there are a large number of individuals in the middle of these two extremes for whom we must modify our prescription of exercise strategy.

⇒What is your patient’s capacity?

We disregard our patients’ ability for exercise when we offer them too many workouts. By giving them extra workouts, we actually boost their desire to do those activities. We must keep in mind that drive is not always a reliable companion.

Consider a patient who has restricted energy levels due to ongoing discomfort, a lack of experience with workout routines, or limited bandwidth. The probability of exercise adherence failure will thus rise if too many workouts are prescribed. The possibility that the patient will benefit from their therapy is decreased when we raise this risk of failure. The Strength of One ,I’ve discovered that offering my patients fewer workouts has helped them get better outcomes from their treatment plan.

Sounds easy enough, doesn’t it? But it may be difficult. I’d want to demonstrate how I streamline the process I use to decide which exercise to provide patients. Less exercise are given, which lowers the level of motivation required from our patients. The chance that they will routinely exercise rises as the “motivation ask” falls. I really support the Power Of One because of this.

The Power of One advocates concentrating on providing your patient only one exercise throughout your evaluation session.

I make an effort to do this with each evaluation. I have to deliver the exercise that will have the most effect since I can only give one activity in that first session.

I develop my diagnostic theory about the patient’s state and the main causes of their symptoms and dysfunction based on the results of my examination. Considering the problem to be biomechanical, I carry out an intervention during the session before doing a retest to gauge its impact.

If my retesting supports my theory, I will give the patient one activity to perform at home that is connected to my intervention. The next session begins with a retest of significant objective data that will aid in providing me with support for my working theory.

⇒Avoid prescribing exercises in a blanket manner

Additionally, I don’t want to prescribe a number of exercises in the hopes that one of them may be effective. The amount of benefit a patient receives from one main exercise is larger if they can complete it properly and consistently than if they are given ten activities to perform unevenly. Giving only one workout offers additional significant advantages.

I make it simple for my patient to achieve by providing only one exercise. Giving the patient one exercise helps him or her gain confidence in carrying out an at-home fitness routine.

Additionally, patients will be more motivated and competent to add additional exercises in subsequent sessions after they see first success, as measured by symptom relief and consistency in doing an activity. Success is contagious.

When you are just dealing with one activity, it is also simpler to troubleshoot habit development with the patient early on in the therapy program. Beginning with only one exercise makes it simpler for the patient to maintain consistency, and it fosters confidence to take on additional or more difficult activities.

Although we don’t only offer our patients one workout, it might be challenging to choose how many exercises to provide them.

⇒Not too little, not too much. exactly right

Exercise overload might result from doing too much.

We run the danger of not advancing the patient as rapidly as feasible if we do too few workouts.

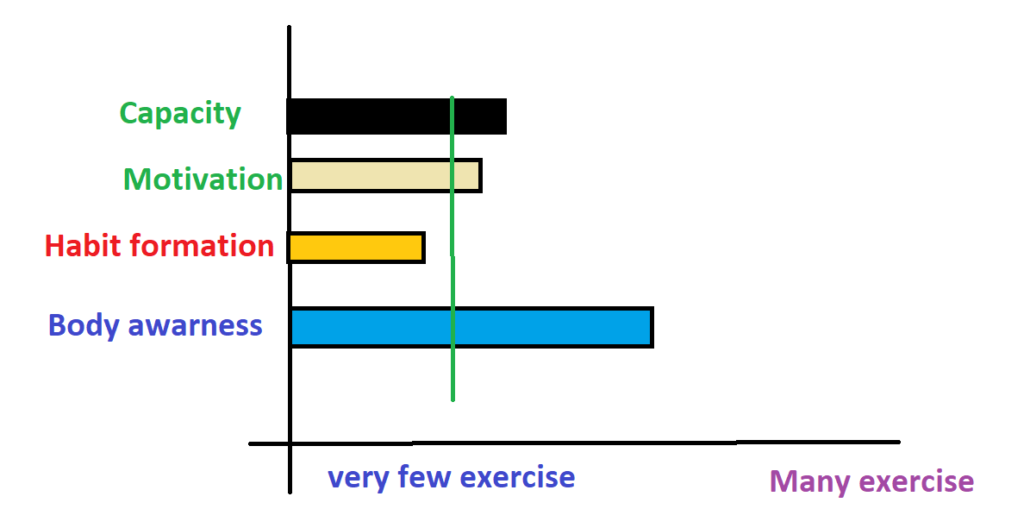

When determining how many exercises to give our patients, there are a few important aspects we need to consider.

Capacity

When recommending exercises, it’s important to take the patient’s capacity—both mental and physical—into account. One’s ability to engage in exercise will be harmed if their capacity is reduced due to discomfort, a lack of social support, or job stress.

We must consider the patient’s level of motivation prior to starting therapy. A high degree of motivation will facilitate starting at-home workouts and facilitate establishing an exercise habit.

Habit Formation

We must take the patient’s capacity for habit formation into account. Patients may need assistance developing new habits and maintaining an exercise regimen. Adding new workouts should be easy for someone who follows a regular exercise or training schedule. But people who struggle with forming new habits or lack confidence may find it difficult to fit in exercise.

Body Awareness

Having excellent body awareness might help one do an activity more effectively. When doing an activity, someone will feel less confident and less successful if they are uncertain of their technique. Before introducing additional exercises, a patient with limited body awareness may need more time and experience with less activities.

You can determine the amount of workouts a patient can undertake satisfactorily by taking into account all four of these variables. If a patient does poorly across the board, you should introduce exercises more gradually and pay closer attention for indications that the patient is finding the exercises difficult.

A patient is more likely to succeed in having a wider set of exercises (or more difficult exercises) to do on a regular basis if they have the mental and physical capability, are driven, have the ability to form good habits, and have a high degree of body awareness.

⇒Accepting a challenge?

Consequently, here is a task for your forthcoming clinical week.

Before you are certain that your patients are doing the exercises you have given them regularly, refrain from offering them more workouts. Try to concentrate on providing the patient only one exercise as you finish a fresh evaluation this week.

Keep in mind that the quantity of exercises you offer your patients does not directly affect their worth or your identity as a therapist.