Three factors to think about while deciding whether to return to sports

Clinicians must be a part of the decision-making process when it comes to getting an injured player back in the game. While they must guarantee appropriate recovery, they also must consider the drawbacks of keeping an athlete from training for an extended period of time. The guidelines should take the demands of returning to sport into account on a physical, physiological, and psychological level. Tracy Ward has discussed the psychological components necessary for a successful return to play. She now concentrates on the physical factors influencing these (1) choices, since balancing the biology of healing with the load exerted on the athlete influences the likelihood of re-injury.

For some of the most typical sports injuries, there is a significant incidence of reinjury. For instance, re-injury rates range from 15% to 25%. (2) (3) (4) 30% of repaired anterior cruciate ligaments (ACLs) are for the repaired groin, 44% are for the Achilles tendon. These levels of reinjury are sometimes linked to an athlete’s desire to return to play too soon, pressure from teams and coaches, ignorance of the level of abilities required to return safely, or a combination of the aforementioned factors.

The wound must heal in addition to being healed. A similar continuum of rehabilitation is advised by research on returning to sport and (5) rehabilitation is not a personal choice based on a few exams completed at the conclusion of a rehabilitation program. The athlete is to undergo rehabilitation in three phases, with each step being followed by evaluation:

- Resuming involvement

- Return to athletics

- Go back to the performance

This phased approach to rehabilitation makes sure the athlete is prepared for the gradually higher demands put on them. The capacity to execute at the appropriate level is improved by gradually exposing individuals to increased demands that test injury healing, rehabilitation integrity, confidence, and decision-making.

Return to sport Testing

A variety of tests are used in return-to-sport examinations to evaluate the amount and quality of limb movement. (6) Experts suggest a limb symmetry index (LSI) of at least 90%. A symmetrical limb operates at 90% of the level of the uninjured limb. Muscle strength testing, jump tests, a clinical examination, the patient’s stated sentiments of preparedness, and performance-based assessments are among the tests that are employed.

Despite the fact that these tests are helpful for assessing the degree of present impairment and the status of rehabilitation, they do not always indicate that the athlete has recovered from their injury or is capable of handling the demands of their sport. Additionally, these impairment tests (5) do not evaluate “open skills” and as a result, have little relevance to engaging in sports. These abilities include the athlete’s capacity to respond to unforeseen circumstances and make choices, particularly when game weariness is present.

Numerous studies also claim that the most important aspect in deciding a return to sport is the amount of time that has passed after the injury. For instance, 85% of studies on the ACL recommended letting athletes to compete nine months after surgery without further treatment (6). Thorough evaluation of the athlete’s physical skills. The significant re-injury incidence of up to 22% within the (6) correlates with this comeback. first 2–5 years after recovery from an ACL operation. (5) But there are now revised guidelines for determining return-to-sport preparedness. They consist of six basic ones.

Deciding factors for return-to-sport requirements

- Use a test battery, or collection of tests.

- Whenever feasible, choose open activities over closed jobs (which are more regulated).

- Include tests that require reactive decision-making.

- Determine your psychological state of sport preparation.

- Track workloads both internally and externally.

Consider the following strategies to help further inform the choice on return-to-sport readiness:

- Framework for StARRT

- Optimal loading recommendations (5)

- The continuum of control chaos(7)

1) The StARRT model

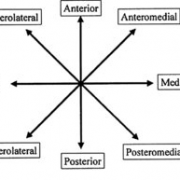

A methodology for estimating the risks of outcomes is called the Strategic Assessment of Risk and Risk Tolerance (StARRT; see picture 1).

connected to a return to sport. A method for risk assessment is provided in the first two phases. The tissue’s health and its capacity to withstand stress are determined by the first stage (health risk). The second step, known as activity risk, examines the tissue stress by examining the accumulated load and the wounded tissue’s capacity to bear it. The risk tolerance modifiers and (5,6) are provided in the third step.

By calculating a final determined risk to the athlete, the cumulative elements that may affect return to sport are estimated.

2) Recommendations for optimum loading

The athlete’s present training load (acute workload) and four weeks’ worth of training (chronic workload) must be carefully considered while monitoring loading throughout recovery.

This content is private. please select our membership plan to unlock the private content features.

Click here

And unlock the content.